Do We Find Our Favorite Books or Do They Find Us Instead?

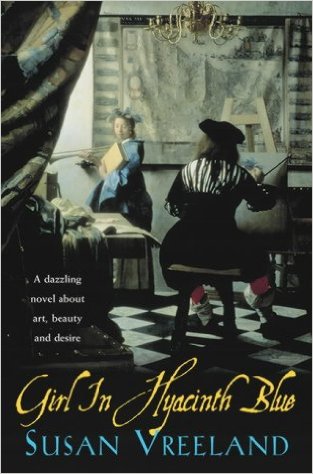

I loved the 1999 book „Girl in Hyacinth Blue” so much that I absolutely had to interview the one who wrote it. Stepping behind the curtains, I discovered the woman behind the girl: an author with an amazing story of her own, who wrote this book as a way of staying alive.

Books, just like people, need to find their own place in this world. They don’t fit just anywhere. The crowd’s lust for Dan Brown novels, Harry Potter volumes or the latest ,,chic lit” creations can be easily satisfied in the white open spaces of big bookstores, with the speakers blasting with the latest radio hits. Susan Vreeland’s books however, feel much more at home in the little bookshop on the corner of the street, the one that’s filled with both the scent of rough old paper and the smell of pristine-printed glossy pages.

You all know it, it’s that vintage bookshop or quiet library where the sound of pages slowly turning is the only soundtrack that fills the silence. The kind of place where I cradled in my hands Susan’s book – ,,Girl in Hyacinth Blue” – for the very first time. I bumped into it while looking for an International Relations textbook in the library of Regent’s College, London, the place where I spent part of my beautiful 20s.

The word „hyacinth” was the one that caught my eye, because you rarely find it in a book title and, most of all, because hyacinths are my favorite flowers in the whole world. I took the book and read the first page, then the first ten… and by the tenth page I was too caught into the storyline to be able to put it back on the shelf again. I took it with me and it revealed itself as one of the loveliest and dreamiest pieces of writing I’ve ever visited.

Vreeland’s novels are not to be read on fast forward, but savored like bonbons from a tiny box of Parisian fine chocolates. They give you a strange yet familiar feeling of coziness and urge you to come back from time to time, for a pageful of comfort or a timely shelter from your daily life. Susan’s books have corners of their own, that you sometimes feel an inexplicable need to revisit.

,,She thought of all the people in all the paintings she had seen that day, not just Father’s, in all the paintings of the world, in fact. Their eyes, the particular turn of a head, their loneliness or suffering or grief was borrowed by an artist to be seen by other people throughout the years, who would never see them face to face. People who would be that close to her, she thought, a matter of few arms’ lengths, looking, looking, looking, and they would never know her”

This excerpt would be my very own ,,corner” in Susan’s book. The character that people will never know is no other than Magdalena, Vermeer’s daughter, whose story finds its place in Vreeland’s ,,Girl in Hyacinth Blue”.

The author retraces Vermeer’s imaginary 36th painting, that wanders around the world, forever changing the lives of people it comes in contact with. From a former nazi officer who steals it during the war and is bound to only admire it in secret, up to Vermeer’s own daughter, Magdalena, who secretly dreams of becoming a painter in her own right and who ends up poor and heartbroken, hopelessly witnessing an auction of her beloved painting.

In the final scene of the book, she agonizes at the thought that all the people around her at that auction, fighting over the painting of the „girl in hyacinth blue” would never recognize the actual girl sitting amidst them, in her sad, worn-out look.

How could they, when the painting showed her in those times when she didn’t yet know that ,,lives end abruptly […] and nice things almost happen”? When she was still beautiful, young, hopeful? Each chapter marks a different story and a different time period, the only detail that brings the novel together is Vermeer’s imaginary painting.

Just like her readers in over 40 countries, Susan Vreeland – a retired 70 years old English teacher from San Diego – has chosen another meaning of the word ,,truth”. Her characters and even the painting may be imaginary, but their inner struggles are so finely depicted and wholeheartedly lived that you cannot help but grow fond of them, a sort of fondness that stays with you forever.

,,There’s a truth about accuracy and mirroring the reality in concrete detail. I do spend a great deal of time getting the facts right, but that alone does not make fine literature”, she explained to me a few years ago, when I contacted her to declare my undying love for her book.

She declares herself faithful to the ,,truth of the person, not the truth about the person” and the fact that she can imagine the stories of people centuries away doesn’t only stem from a vivid talent, but also from a place of fear and death. A different, easier, fate would have never brought her in the position of keeping the one promise made to herself more than 40 years ago.

,,Coming out of the Louvre for the first time in 1971, dizzy with new love, I stood on Pont Neuf and made a pledge to myself that the art of this newly discovered world in the Old World would be my life companion” she remembers. ,,Girl in Hyacinth Blue” came to life three decades after the Pont Neuf epiphany and several months after Susan herself had been given a new take on life, recovering after an aggresive form of cancer.

During her illness, being constantly on pain medication, it was difficult to read, so she found a different consolation. She discovered that she could look at paintings in art books, imagining the lives of the people in them and wondering about what relationship they could have had with the one who painted them. So she did that, hours on end, for months and months. ,,My books are my way of thanking the artists who have enriched my life and, I might even say, who saved my life”, she explained to me, with a form of sweetness and humbleness that I profoundly admired.

In 1999, when her ,,Girl in Hyacinth Blue” came out, over 50.000 books went to print in the USA. Now, 17 years later, more than 500.000 volumes come out yearly, so competition is fierce. ,,Publishing houses, just like filmmakers, want content full of intrigue, action, sex, violence or at least an ,,arrived” celebrity that they feel will sell more easily” she admits. ,,It’s harder to interest people in a quiet novel”.

Nevertheless, she continues to write books, all inspired by the imaginary life of people in paintings or the inner struggles of artists: ”Luncheon of the Boating Party” (inspired by Renoir’s painting with the same name), „Clara and Mr. Tiffany” (the story of the woman who designed the famous Tiffany lamp), „The Passion of Artemisia” (the secret life of Artemisia Gentileschi, one of the most talented baroque paintors), „The Forest Lover” (the imaginary story of one of the first post-impressionist Candian paintors, Emily Carr) or „Life Studies” (a volume on the true lives of impressionist and post-impressionist paintors, as told by people who knew them).

The beautiful niche she found suits her and, more importantly, it’s hers to own. Or at least half of it. The other half belongs to Tracy Chevalier, whose ,,Girl With A Pearl Earring” (inspired by Vermeer as well) came out – coincidentally – the same year as ,,Girl in Hyacinth Blue”. ,,We feel kindly to one another” admits Vreeland, „like a sense of solidarity„. This shows especially at times when readers mistake one for the other and ask her to sign the wrong book. ,,I would sign <For Mary Smith, best wishes from Tracy Chevalier via Susan Vreeland>” she smiles. In order for the reader not to feel embarrassed when reading the inscription, she makes sure to add that the book will now become a collector’s item.

Some of my favorite quotes from „Girl in Hyacinth Blue”:

On the secret emotions of painted characters:

„Standing up as if to go, the muslin in my hand, I couldn’t keep my eyes from the girl in the painting. What I saw before as vacancy on her face seemed now an irretrievable innocence and deep calm that caused me a pang. It wasn’t just a feature of her youth, but of something fine – an artless nature. I could see it in her eyes. This girl, when she became a woman, would risk all, sacrifice all, overlook and endure all in order to be one with her beloved”

On paintings having a life of their own:

„When my trunks were loaded and I was helped into the coach, what I felt was not a weeping, but a longing to weep that I mastered all to easily. Gerard would survive, and thrive. If there was anything to weep for, it wasn’t Gerard, or Monsieur le C, or even me. It was the painting, for now it would go forth through the years without its certification, an illegitimate child, and all illegitimacy, whether of paintings or of children or of love, ought to be a source of truer tears than an I could muster at parting”

On knowing someone you don’t really know:

„Now it became clear to her what made her love the girl in the painting. It was her quietness. A painting, after all, can’t speak. Yet she felt this girl, sitting inside a room but looking out, was probably quiet by nature, like she was. But that didn’t mean that the girl didn’t want anything, like Mother said about her. Her face told her she probably wanted something so deep or so remote that she never dared breathe it, but was thinking about it there, by the window. And not only wanted. She was capable of doing some great wild loving things”

And my favorite quote, Magdalena Vermeer’s heartbreaking monologue:

Still a woman overcome with wishes, she wished Nicolaes would have come with her to see her in the days of her sentry post wonder when life and hope were new and full of possibility, but he had seen no reason to close up the shop on such a whim.

She walked away slowly along a wet stone wall that shone iridescent and the wetness of the street reflected back the blue of her best dress. Water spots appeared fast, turning the cerulean to deep ultramarine, Father’s favorite blue.

Light rain pricked the charchoal green canal water into delicate, dark lace, and she wondered if it had ever been painted just that way, or if the life of someone as inconsequential as a water drop could be arrested and given to the world in a painting, or if the world would care…”

So happy you chose to share your thoughts in English too! ❤️ Will read this book, it seems interesting and charming. Good luck, Diana 🙂